Rubber duck physics

or how everything is a prop for teaching if you look hard enough.

This post started life as a CPD workshop, which, in turn started as a flippant comment - “Anything can be a good teaching tool, with imagination you could teach half the course with a rubber duck”. Also hidden in here is a bit about rubber duck debugging - a bit of metacognition that I think we should all be using. I hope that this post entertains, gives you something useful and makes the point that it doesn’t all have to be so serious… So here goes:

A qu(a)(i)ck history:

The rubber duck is a much newer invention than people tend to assume, and its history is tied closely to changes in materials rather than to childhood culture itself. Before the late nineteenth century, toys that could survive water were rare. The development of vulcanised rubber made it possible to mass-produce waterproof objects, and by the end of the 1800s solid rubber animals and boats were being sold as novelties. These early toys were heavy, sank in water, and were not really designed with bathing in mind.

Duck-shaped toys began to appear in

the early twentieth century, largely because ducks were familiar animals and naturally associated with water. However, they still looked quite realistic and were often solid. The modern rubber duck only became possible after the Second World War, when manufacturing techniques allowed toys to be made hollow and lightweight. This meant they could float, be brightly coloured, and include simple squeakers. By the 1950s, the yellow, floating, squeaky duck had become a standard bath toy in Europe and North America

.

Its place in popular culture was cemented in 1970, when Ernie sang “Rubber Duckie” on Sesame Street. That moment turned the duck from an ordinary toy into a symbol of comfort, routine, and childhood itself. From then on, the rubber duck appeared everywhere, often with no reference to bathing at all.

As a Model of the complexity of the universe

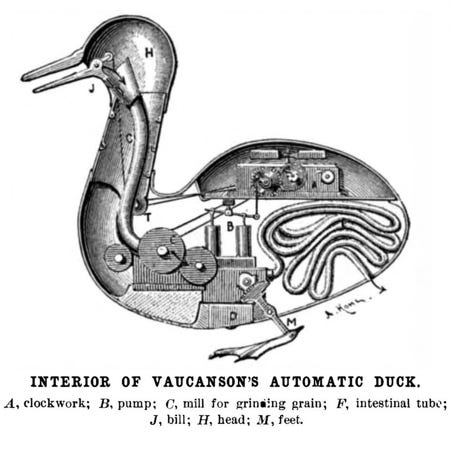

Vaucanson’s mechanical duck is an early and revealing example of the belief that the complexity of the natural world could be captured, and even reproduced, through machinery. Built in 1739, the duck was not intended as a toy but as a philosophical statement. At a time when Enlightenment thinkers were increasingly viewing the universe as a kind of vast mechanism, Vaucanson set out to show that a living creature might be understood as nothing more than a very intricate machine.

The duck appeared to eat grain, digest it, and excrete waste. To contemporary audiences this was astonishing, not simply because of the craftsmanship involved, but because of what it implied. If the processes of life could be imitated through gears, bellows, and pipes, then perhaps life itself was governed by knowable, mechanical laws. In this sense, the duck functioned as a miniature model of the universe: complex, ordered, and operating according to hidden but intelligible mechanisms.

Of course, the duck was also a kind of illusion. Its “digestion” was largely a trick, with pre-prepared material stored inside and expelled at the appropriate moment. Yet this does not undermine its significance. The point was not perfect biological accuracy, but the demonstration that outward complexity could arise from internal structure. The audience was invited to believe that, given sufficient ingenuity, even the most mysterious processes might be reduced to mechanical explanation.

Seen this way, Vaucanson’s duck anticipates later scientific models and simulations. Like modern climate models or computational representations of ecosystems, it simplified reality while claiming to reveal its underlying logic. The duck did not truly replicate life, but it embodied the Enlightenment confidence that the universe itself might be understood as a system of parts, interacting predictably, and ultimately comprehensible.

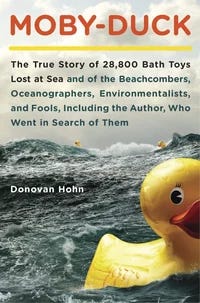

A Container spill and ocean currents

The spill of rubber ducks into the Pacific Ocean is often cited as a neat illustration of how accidental events can become natural experiments. In 1992, a cargo ship lost a container carrying thousands of plastic bath toys—mostly ducks, but also turtles, frogs, and beavers—into the open ocean. Released from their commercial purpose, the toys entered a system far larger and more complex than any shipping route: the global circulation of the oceans.

As the toys began to wash up on beaches years later, their appearances seemed at first random. Ducks turned up in Alaska, then along the west coast of North America, and eventually in the North Atlantic and even near the Arctic. What emerged, however, was a visible trace of ocean currents operating over long timescales. The toys drifted with surface currents, were caught in gyres, and in some cases frozen into sea ice before being released again years later. Their slow dispersal made concrete what is otherwise abstract: the oceans are not static bodies of water, but dynamic systems with structure and flow.

Oceanographers were able to use the reported sightings to test and refine models of surface circulation. The ducks did not provide precise data, but they offered something equally valuable: an intuitive, physical marker of a complex system. Like dye injected into a laboratory flow tank, they revealed patterns that are normally invisible, linking distant parts of the world through continuous motion.

In this sense, the rubber duck spill sits comfortably alongside other attempts to model complex systems. It did not simplify the ocean into a machine, as Vaucanson’s duck had simplified life, but it allowed observers to glimpse the organising principles of a vast and messy system. The ducks became moving proxies for currents, demonstrating how simple objects, once released, can map the hidden order of a complex universe.

Glacial run off with…

There was an actual scientific experiment in which rubber ducks were deliberately used to try to trace glacial runoff — and we know when it happened.

In August 2008, scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory released about 90 rubber bath toys into meltwater moulins (vertical meltwater channels) in the Jakobshavn Glacier on the west coast of Greenland. The idea was that the ducks, floating in the meltwater, might travel through sub-glacial channels and eventually emerge in nearby fjords or Baffin Bay, potentially revealing something about how meltwater flows under the ice and how it affects glacier motion. Each duck was marked with a note offering a reward and an email address so finders could report where and when they appeared. Scientific American

The hope was that sightings would be reported over time, but none were ever confirmed, likely because many became trapped in internal glacial aquifers or simply were never found in the remote regions where they might have surfaced.

Spurious explosion content:

As a point of reference in Waves:

To illustrate Superposition:

To add humour to Barton’s pendulum:

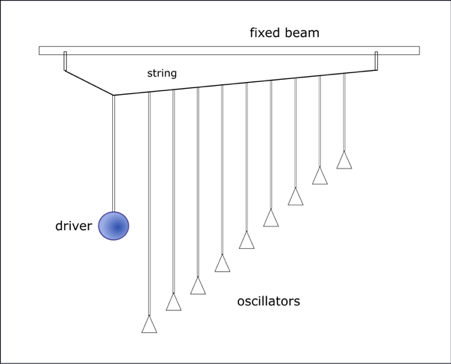

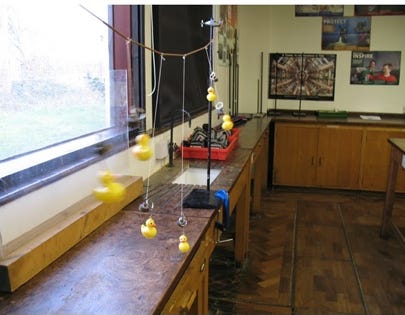

Barton’s pendulum consists of several pendulums of slightly different lengths suspended from a common horizontal support. When the support is driven with a periodic motion, energy is transferred through it to all the pendulums, but only one (or a small group) responds strongly. That pendulum is the one whose natural frequency matches the driving frequency of the support. The others move only weakly. It’s set up as follows;

Where the oscillators need to be light, and the driver a lot heavier. As to what to use for the oscillator - I struggled for years to find the perfect thing, as they need to be more-or-less identical until:

Rubber Duck Debugging in the Physics classroom

In software engineering, rubber duck debugging is a method of debugging code. The name is a reference to a story in the book The Pragmatic Programmer in which a programmer would carry around a rubber duck and debug their code by forcing themself to explain it, line-by-line, to the duck.

Rubber duck debugging in the classroom is a simple but powerful strategy that encourages learners to solve problems by explaining their thinking out loud. The idea comes from computing, where programmers talk through their code line by line to a rubber duck in order to spot mistakes. In a classroom, the duck is symbolic rather than essential; what matters is the act of verbalising reasoning in a clear, step-by-step way.

When students explain their work aloud, they are forced to slow down and make their thinking explicit. This process supports metacognition, as learners monitor their own understanding and often notice errors, assumptions, or missing steps without any external intervention. The technique also reduces cognitive load by breaking complex tasks into manageable chunks and takes advantage of the well-established self-explanation effect, where learning is strengthened through explanation rather than passive review.

In practice, rubber duck debugging can be introduced by modelling it first. A teacher might deliberately work through a flawed example while “explaining” it to an object on the desk, highlighting how the explanation itself reveals the mistake. Students can then use the technique independently or in pairs. In paired work, one student acts as the “duck” and listens silently while the other explains their thinking; the key rule is that the listener does not help, prompt, or correct. This keeps the focus on self-correction rather than peer tutoring.

Although closely associated with programming, the approach transfers well to other subjects. In mathematics, students can talk through each algebraic step or justify why a particular method is appropriate. In science, they might explain an experimental method or the reasoning behind data processing. In essay writing, reading a paragraph aloud and explaining the purpose of each sentence often exposes weaknesses in argument or structure. In physics, verbalising assumptions, formula choices, and units can quickly reveal conceptual misunderstandings.

Rubber duck debugging works best when it is low-stakes and time-limited. Short, focused periods encourage students to attempt problem solving independently before seeking help, building resilience and confidence. It is also inclusive, supporting learners who benefit from slower, more deliberate processing or from practising academic language in a safe context.

Overall, rubber duck debugging is less about the novelty of a duck and more about creating space for students to think aloud. By making reasoning visible, it helps learners become more independent, reflective problem solvers.

Salter’s Duck

Developed in the 1970s by Stephen Salter, the device was proposed as a way of extracting energy from ocean waves. Superficially, it looks almost comic: a cam-shaped floating body that rocks back and forth with the motion of the sea. Yet behind the playful appearance lies a serious attempt to model and harvest one of the most complex energy systems on the planet.

The key idea was resonance and coupling. The duck was designed so that its natural motion closely matched the dominant frequencies of ocean waves. As waves passed, the duck would “nod,” converting that motion into hydraulic pressure and then into electrical energy. In theory, an array of ducks could absorb a large fraction of the energy in incoming waves, far more efficiently than earlier wave-energy devices. The sea, chaotic and variable, was being addressed not by brute force, but by tuning.

What matters conceptually is that Salter’s Duck treated the ocean as something that could be partially understood and negotiated with, rather than controlled. The device did not resist the waves; it yielded to them in a carefully constrained way. Like Barton’s pendulum, it relied on selective response rather than uniform motion. Like the drifting rubber ducks, it used floating bodies to make sense of large-scale flows. The duck became a mediator between a vast natural system and human-scale engineering.

Although Salter’s Duck was never deployed at full commercial scale, largely for economic and political reasons, its significance lies in the approach it embodied. It assumed that complex systems could be engaged through well-chosen simplifications, and that form, motion, and frequency mattered as much as raw power.

The Waddling Duck

is a toy which “walks” down an inclined slope with a forward-backward rocking motion. The toy consists of a body with a body-fixed front leg and freely rotating rear leg, which is hinged to the body.

The toy is modeled with four degrees of freedom: the displacements and rotation of the center of gravity of the body with respect to the inclined slope and the rotation of the rear leg. The rotation of the rear leg is constrained by the front leg and a stop. The legs have an identical (mirrored) shape. The feet have a tread described by a circle segment. Sliding motion is observed in the actual toy. No restitution after impact is observed for the actual toy. The impacts are therefore modeled as completely inelastic.

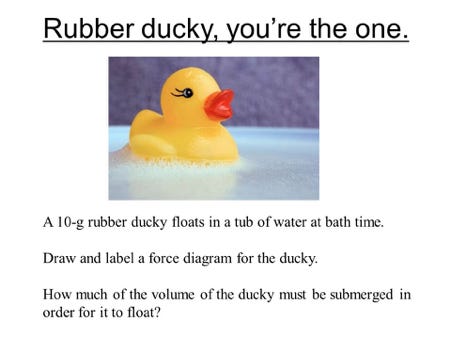

As an example of forces

Rubber ducky, you’re the one. A 10-g rubber ducky floats in a tub of water at bath time. Draw and label a force diagram for the ducky etc…

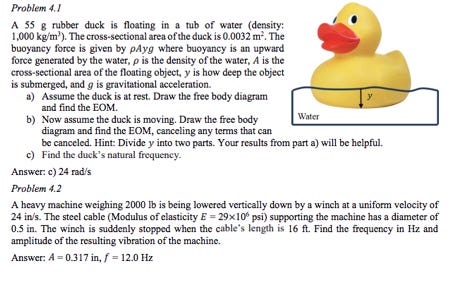

A harder problem:

In X-rays

I see your pregnant dog xray and raise you a rubber ducky dog xray : pics

In Fermi-problems and scale questions:

The ‘World’s Largest Rubber Duck‘ is more than six stories high, 79 feet wide, 80 feet long and weighs over 30,000 pounds. Somehow this pops up in my lessons occasionally.

As an example of genetics

Wild ducklings, like these baby Mallard ducks, are in fact typically only partly yellow:

Picture

Photo by TheBrockenInaGlory via Wikimedia Commons, used under the CC-By-SA 3.0 license.

While I’m no expert, I would guess that the mottled yellow-brown coloring of the juveniles is, at least partially, protective coloration, just like the somewhat similar pattern on the adult female’s feathers. While it may appear conspicuous on open water, ducks in their natural habitat will often seek shelter among reeds and other vegetation, where the irregular pattern of light and shadow would create a very effective camouflage for the ducklings.

As for the all-yellow ducklings of domestic ducks, these presumably arose via elimination of the darker parts of the coloring as a result of selective breeding, perhaps as a side effect of artificial selection for the white adult plumage found in many domestic ducks today.

Specifically, according to a recent study of domestic duck genetics, it appears that the all-white plumage of domestic Pekin ducks is caused by a single recessive mutation to the MITF gene, which regulates melanin production. The mutation, when homozygous, causes the normal melanin production pathway in the skin to be almost entirely shut off, so that the adult plumage is pure white regardless of what other plumage color genes the bird may be carrying (a fact apparently known for a long time from cross-breeding experiments, even though the specific mutation behind this effect was not determined until recently).

Apparently, however, the yellow base pigmentation in young ducklings is not affected by the MITF mutation, and thus appears even in individuals homozygous for it. Presumably this is because the yellow color is produced via some other pathway, which is active in young ducks but gets shut off as they develop their adult plumage. The brown pigmentation pattern overlaid on top of it in wild-type ducklings, however, is controlled by MITF, and thus fails to appear in ducklings with two copies of the mutated version of the gene, leaving their juvenile plumage pure yellow.

As far as I can tell, the specific reason why the yellow pigmentation in ducklings is not controlled by the MITF gene still remains unknown. Or, if it is known, my Google search skills were not good enough to find it.

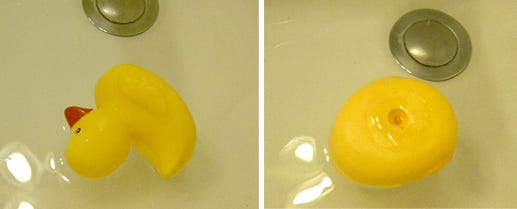

Center of mass and stability

A capsizing rubber duck provides a compact way of thinking about stability and centre of mass without resorting immediately to equations. When the duck is upright in the water, its centre of mass lies below the centre of buoyancy. In this configuration, any small tilt produces a restoring moment: the buoyant force acts upward through a point that shifts with the shape of the submerged body, while the weight acts downward through a fixed point. The separation of these forces creates a torque that returns the duck to its original orientation.

If the centre of mass is raised, by adding a weight higher up or redistributing mass unevenly, this balance changes. A small tilt may no longer produce a restoring moment. Instead, the torque can act in the opposite direction, increasing the tilt. At that point the upright position becomes unstable, and the duck will capsize. The transition from stable to unstable does not require dramatic changes in shape or force, only a subtle rearrangement of where the mass is concentrated.

What makes the rubber duck useful is that the geometry is easy to see. As the duck tips, the submerged volume shifts sideways, moving the centre of buoyancy. Whether the duck rights itself or overturns depends on whether the line of action of the buoyant force passes to one side or the other of the centre of mass. This is the same principle that governs the stability of ships, floating platforms, and even people standing upright.

Seen in this way, the capsizing duck is not a novelty demonstration but a small model of a general rule. Stability is not about absolute weight or size, but about relative positions and how forces respond to displacement. The duck makes visible the idea that equilibrium can be stable, unstable, or marginal, and that which one applies depends entirely on the geometry of mass and buoyancy.

Doppler the duck

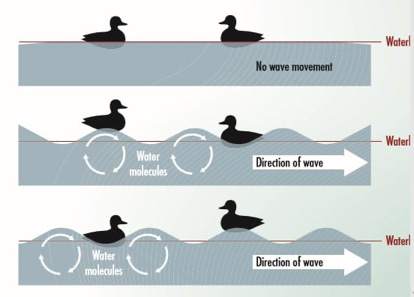

A swimming duck makes the Doppler effect visible in a way that avoids most of the usual abstractions. Imagine a duck moving steadily across a pond while producing a regular disturbance in the water — a small wake, a pulse, or even an audible quack. The duck is both the source of the waves and an object moving through the medium.

As the duck swims forward, each new wave is emitted from a position slightly ahead of the previous one. In front of the duck, the wave crests are compressed, arriving more frequently at any fixed point. Behind the duck, the crests are stretched out, arriving less often. To an observer watching from the bank, the pattern is immediately asymmetric: tightly packed ripples ahead, widely spaced ripples behind. This is the Doppler effect in its most concrete form.

If the duck increases its speed and eventually moves faster than the waves it produces, the situation changes qualitatively. The waves can no longer spread out in front of the source. Instead, they pile up along a sharp boundary, forming a V-shaped pattern or cone of waves trailing behind the duck. Every wave emitted lies on this boundary, because the duck has outrun its own disturbances. This is the water-wave analogue of a shock wave.

The cone marks the transition from simple Doppler shifting to a fundamentally different regime. Below the wave speed, the pattern is merely distorted; above it, the waves reorganise into a coherent structure. The angle of the cone depends on the ratio of the duck’s speed to the wave speed, shrinking as the duck goes faster. In this way, the pond becomes a record of motion, showing not just that the source is moving, but how fast it is moving relative to the waves it creates.

Subatomic particles

The Myth of the echoless quack

The myth of the echoless quack is a useful reminder of how easily gaps in experience turn into claims about reality. The story goes that a duck’s quack does not produce an echo, a fact that is often presented as curious, counter-intuitive, and faintly mysterious.

Like many such claims, it persists not because it is true, but because it is rarely tested in circumstances where an echo would actually be noticeable.

In practice, ducks do produce echoes. Their calls obey the same physical laws as any other sound. What makes the myth plausible is a combination of context and expectation. Ducks are usually heard outdoors, near water, in open spaces with few hard reflecting surfaces. Echoes require delay and reflection, and in a flat, absorbent environment the reflected sound is weak and arrives too quickly to be perceived as distinct. The absence of a noticeable echo is not a property of the quack itself, but of the surroundings in which it is heard.

There is also a perceptual element. A duck’s quack is short, noisy, and broadband. Any reflected sound tends to blur into the original rather than standing out as a clear repetition. Longer, sharper sounds, like a shout or a clap, make echoes easier to detect. The myth survives because people expect echoes to sound theatrical, and when they do not, they assume they are not there at all.

In this sense, the echoless quack sits comfortably alongside other duck-related misunderstandings. It reflects a tendency to attribute special properties to familiar objects when the explanation lies instead in systems, environments, and limits of observation. The duck does not defy acoustics; it simply reveals how much of physics depends on context. The echo is missing not because the sound is strange, but because the conditions needed to hear it are.